Part 4 in the story of “Uncle Len, Wife-Killer”

Samuel Leonard Thomas Ashworth had his charge reduced from murder to “unlawful killing of his wife” on November 16th, 1960 by the Magistrates Court in Maidenhead. The hearing lasted three hours, the magistrates only needed 10 minutes to come to the conclusion that there was no evidence of aforethought in the killing, nor was their express malice1. At this time, murder carried the death penalty. Len was charged with manslaughter (note that the word uses “man” generically).

Would the killing of Lisbeth Ashworth nee Frank nowadays be considered to be a case of femicide? The term is only in recent years more frequently used, partly to increase awareness of how often women are killed by men. In around 40% of all killings of women, the spouse is the killer2.

The word was first ever used in 1801 by an Irish historical writer called John Corry in “A Satirical View of London at the Commencement of the 19th Century”3. But not until 1976 was the term publicly in use, at the International Tribunal of Crimes against Women, by Prof. Diana E. H. Russell. She defined femicide as the “murder of women by men motivated by hatred, contempt, pleasure or a sense of ownership of women”. She posited that the term could also be used to highlight “the way states or governments are unresponsive to or complicit in, the killings of women and girls”4.

Femicide is used nowadays to highlight the inequality in power between the sexes. In cases where stereotypical gender roles and social norms played a harmful role, femicide can be a useful term to underscore this. Is it useful to take another look at Lisbeth’s killing and ask whether the social norms of the time―that Lisbeth was seen to have a marital duty to look after the children and Len, although absent most of the time, posted abroad, was still held to be a “devoted father”?

Desmond Ellis and Walter Dekesedery narrowed the definition to include intent. They did not think that “slip-ups in a power struggle in which men want to control women, deprive them of their liberty or where women were striving for autonomy”, constituted femicide5. Could this case be such a “slip-up” because Len had not intended to kill Lisbeth? We cannot know if he decided to do away with her when he realised she wanted his children adopted―if indeed that is true―but the lack of evidence of intent was sufficient for the murder charge to be dropped.

The term “intimate partner” or “romantic” femicide has also been used to cover the murder of a woman by her intimate partner, be it boyfriend or husband6. Men who are at high risk of commiting femicide were often abused as children, had previously threatened to commit suicide or murder, exhibited jealousy, abused alcohol or drugs, and attempted to control a woman’s freedom. The presence of firearms and intoxicating substances increased these risk factors. Women who suffered from domestic abuse were at a higher risk of being killed7.

Again, there is no evidence (that I know of, however the record is closed till 2060) that Len suffered from any of the above-mentioned problems or had abused Lisbeth previously, or any of his former wives. Indeed, the prosecution, Mr. Ryder Richardson, paints a very positive picture indeed when talking about Ashworth’s second marriage to Pat: “There is no doubt that this man was a good husband to his wife, and a devoted father to his six children, and they made a happy and united family.”8

But what of the media and societal norms? “In cases of femicide, media reports often suggest that the male was “driven” to commit femicide , due to a breakdown in love attributed to the female”9. The defence of provocation is often used to reduce the time male killers serve in prison.

Reading through the newspaper articles on the murder, Len’s defence is generously quoted. The prosecution less so but then, Mr. Ryder Richardson seemed to have quite a high opinion of Ashworth. Len is repeatedly portrayed as a devoted father who had “kept house” and looked after his children himself, following his second wife’s death10. No-one seemed much interested in what Lisbeth’s point of view might have been, or if they were, it was not reported. The articles present a picture of a foreign woman, cold and calculating, who did not want to do what her husband required of her, and that she had promised him only months before. Instead, she had (unreasonably) objected to looking after eight children on her own in a 3-bedroomed house. Len’s claim that she was “used to a higher standard of living” and that she had allegedly said to him “she was not going to lower her standards”11 makes her out to be a spoilt upper middle class woman down on her luck who had taken in a poor soldier, desperate for a mother for his children. The descriptions in the media made her sound unloving and hard, telling Len “not to be sentimental” about the idea of losing his children12.

Only one newspaper tries to tell Lisbeth’s story of how she escaped to England at 16 from the Nazis when they took over Austria, how both her parents were murdered by them; the man she married and had two children with had died only five years previously. She was a working woman, a nurse; the house belonged to her, not Ashworth, bought with her own money. This was a woman who was used to autonomy who had turned her life upside down for a man, who then killed her.

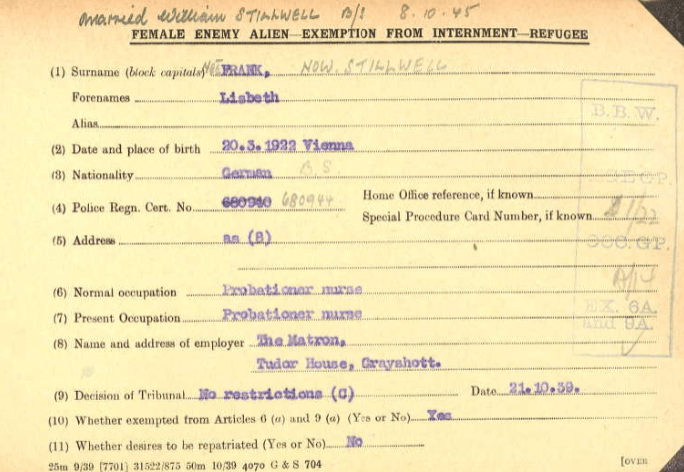

Which of these stories is the true one is hard to tell. But looking back on this time at the beginning of the sixties, a woman’s place was very much in the home, looking after the children. And it was only 15 years after the end of a brutal world war that had cost millions of lives, in which Len had fought and afterwards remained a soldier, posted in former enemy territory. And he was married to an “enemy alien” who, although she had been exempted from internment in 193913, was an Austrian-Jew, and was still to all intents and purposes considered to be a German.

My stepmother’s description of Len as an “easy-going, cheerful chap” on briefly meeting him at a funeral indicates that he won people over relatively quickly. That Lisbeth was prepared to marry him so quickly and agree to massively over-extending herself to make a “happy family” suggests that he was charismatic and persuasive. But when she was faced with reality, alone in Fairacre, and the prospect of moving with him, as a “German”, into an Army barracks, in the country that had exterminated her parents, it is not surprising she wrote to him that she was feeling “far from well”14.

Of course, Lisbeth’s death at Len’s hands does not need to be labelled a femicide to make it shocking and horrific. It is also the story of two completely desperate people whose lives were terribly tragic. They had both suffered extreme loss and were stuck with an untenable situation with eight children. It is totally understandable that Len did not want to lose his children. It is just as understandable that Lisbeth did not want to go to Germany with him. What remains completely incomprehensible, is why he turned on her and took her life. A woman against a soldier, her chances were less than none.

This post is part of an A-Z challenge, to publish a post each day in April on a theme of my own choice. The post was updated and properly sourced on 16 Dec 2025.

This is the story of how Uncle Len killed his third wife, Lisbeth. Previous posts are “A is for Ashworth”, “B is for Berkshire, Basingstoke, Burnley”, “C is for Care of the Children” and “D is for Dinah”.

Coming up: G is for Germany

Sources

- Maidenhead Advertiser, 18 Nov 1960. “Murder Charge Reduced to Manslaughter”, Maidenhead magistrates were told by Mr. John Wood, defending, that there was no evidence of expressed malice or intent to kill. ↩︎

- Garcia-Vergara E et al.: “A Comprehensive Analysis of Factors Associated with Intimate Partner Femicide: A Systematic Review”. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 19 (12): 7336. doi:10.3390/ijerph19127336. PMC 9223751. PMID 35742583, 15 Jun 2022 ↩︎

- Canadian Femicide Observatory for Justice and Accountability: History of the Term Femicide. No date given, accessed on 16.12.2025 https://femicideincanada.ca/what-is-femicide/history/ ↩︎

- Russell DEH: Defining Femicide, Speech to UN Symposium on Femicide, 26.11.2012. Accessed on 16.12.2025 https://www.dianarussell.com/f/Defining_Femicide_-_United_Nations_Speech_by_Diana_E._H._Russell_Ph.D.pdf ↩︎

- Ellis D, Dekesedery W: The wrong stuff: An introduction to the sociological study of deviance. Ontario: Allyn and Bacon, 1996. ↩︎

- Ferguson C; McLachlan F: “Continuing Coercive Control After Intimate Partner Femicide: The Role of Detection Avoidance and Concealment”. Feminist Criminology. 18 (4): 353–375. doi:10.1177/15570851231189531. hdl:10072/430101. ISSN 1557-0851, December 2023 ↩︎

- Monckton Smith J: Murder, Gender and the Media: Narratives of Dangerous Love. Palgrave Macmillan, 2012. ↩︎

- Liverpool Echo: 13 Jan 1961: “Father of Six Accused of Murder Dispute Over Children DEVOTED”. There is no doubt that this man was a good husband to his wife, and a devoted father to his six children, and they made a happy and united family. ↩︎

- Monckton Smith J: Murder, Gender and the Media: Narratives of Dangerous Love. Palgrave Macmillan, 2012. ↩︎

- Daily Herald, 17 Nov 1960. “Devoted father ‘killed wife’”. Ashworth, a devoted father, had an obsession to keep his family together. He kept house and looked after them himself for six months. ↩︎

- Daily Mirror, 14 Jan 1961. “He killed wife who said ‘give away the children’”. But an argument arose between Ashworth and Lisbeth about the children’s future. She said: “I do not intend to be marooned with your children in Germany.” (…) Ashworth, in evidence, told the jury: “Lisbeth was used to a high standard of living. She said she was not going to lower her standards and that we couldn’t afford to keep all the children.” ↩︎

- Maidenhead Advertiser, 18 Nov 1960. “Murder Charge Reduced to Manslaughter”. In a statement made to the police on October 16, Ashworth is alleged to have said: “Last night she was talking about my children being adopted and said I wasn’t to be sentimental about it, it was an easy matter. I ask you – an easy matter to get rid of one’s children.” ↩︎

- UK, World War II Alien Internees, 1939-1945, The National Archives; Kew, London, England; HO 396 WW2 Internees (Aliens) Index Cards 1939-1947; Reference Number: HO 396/241, Name: Lisbeth Stillwell; Gender: Female; Nationality: German; Birth Date: 20 Mar 1922; Birth Place: Vienna, Austria; Description: 241: Dead Index (Wives of Germans Etc) 1941-1947: Stern-Tscher. ↩︎

- Daily Mirror, 14 Jan 1961. “He killed wife who said ‘give away the children’”. A letter written by Lisbeth to Ashworth while he was in Germany was read in court. In it she said: “I have never worked so hard in my life and I feel far from well.” ↩︎

Leave a comment